THE FAVORITE MASTERING TOOLS OF MATT DAVIS

Please tell our readers a little bit about your background.

I’m a mastering engineer/acoustic engineer at Hacienda Mastering and Hacienda Acoustics, based out of Orlando, Florida. I am a graduate of University of Miami’s Music Engineering undergraduate program with a focus on electrical engineering, and NYU’s Music Technology graduate program. I’ve assisted Bob Katz at Digital Domain for the past four years, and am a lecturer at Full Sail University.

What is your favorite piece of hardware gear to work with and why?

My sound system and the listening environment I’ve designed for it to live in are the greatest assets to my studio and inform more of the outcome than any specific processor in my desk. In terms of transfer processors, my GOLY PG-808 sees more use than anything else in my desk. It’s an extremely versatile and sneaky EQ that I feel is equally at home on purist material as it is on club bangers.

Is there a specific VST plugin that radically changed your workflow?

Not drastically, no. In terms of workflow improvements I’ve been really liking Nugen MasterCheck for auditioning codec overshoot for different platforms before cutting the master. The time saved is minimal, but not having to render masters out of my DAW and test them through downsampling to establish post-encode overshoot definitely removes some guesswork.

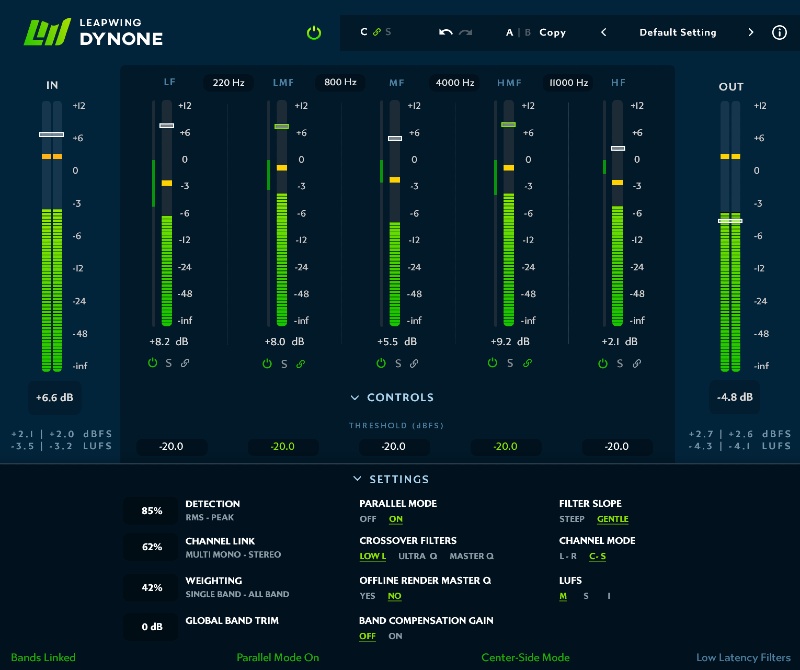

Leapwing Audio’s DynOne saved me from having to buy a TC System 6000, which would have radically changed my bank account for the worse. I’ve been using DynOne since beta of v1, and it has been my go to tone density tool from the first time I auditioned it on a track. With subtle settings it can embellish the front-to-back imaging in a very natural sounding way, with more extreme settings it can play the role of a multi-band maximizer, and I feel it excels equally at both. Don’t expect it to play nice without a damn good CPU though, I’ve upgraded computers more than once now to keep up with the DSP load incurred by DynOne and now DynOne3. Still much cheaper than the TC6000 though, and every bit as good!

Your opinion: Louder is better? Or not? What’s your ideal loudness level for dance music tracks?

From a psychoacoustic perspective yes, louder is objectively better, with the caveat of all other variables being controlled for. If you play the same program material for a listener at different monitor levels they will prefer the higher level version, this will be as true of untrained listeners as it will be for seasoned critical listeners. This is the reason that calibrated monitor levels and offset controls (for equal level A/B’ing of different stages in the transfer path) are found in any competently designed mastering room, you can’t train your way around that intrinsic subconscious preference. Even with seasoned mastering engineers it will bias your preference every time.

Let’s talk about some things that I don’t think are better though. Needlessly high distortion figures aren’t better. Loss of front to back soundstaging isn’t better. Cutting meaningful frequency ranges which evoke involvement and warmth out of the program material for purely utilitarian perceptual loudness reasons isn’t better. Choosing between a narrowed stereo image or a wandering center image isn’t better. All of these are ramifications/requirements of chasing a program level beyond the point of diminishing returns and they are all rampant in the more loudness intensive genres. Louder as a general concept is better, but in the context of mastering there is always a price to pay and a point beyond which the negative ramifications outweigh the positive. Mastering is the art of moderation and the search for truth, I don’t believe a “more is better” mantra is appropriate for any aspect of the craft.

My ideal loudness level for a club track is the one that sounds big when my monitor controller is set to -11dB on a K-20 calibration. The reader is probably disappointed that my response wasn’t a LUFS or RMS value, and believe me if there was a magic number within those metrics that worked every time I would be sharing it here since it would be trivial to reverse engineer from analyzing my work (and I invite you to go see for yourself). But there isn’t a magic number because LUFS is loosely (at best) correlated to our perception of loudness. RMS (from which LUFS is derived) is even less meaningful in that regard.

The contention of LUFS being a loudness metric is highly dependent on consistent energy and density through the audible band, which is very often not the case at all. Try putting a band limited lofi techno track against a more balanced techno track at the same LUFS value and I’m sure you’ll see what I’m talking about. Also, try comparing that same balanced techno track to an acoustic duo/trio at that same LUFS level. The less dense arrangement and inherent acoustic advantage of the latter will make for a signal that is much…much louder at equivalent LUFS values.

I do use LUFS in my process, but only as a diagnostic metric, I know that it has a roll off in sensitivity with a corner frequency around 65hz and I know it has a shelf boosted sensitivity to upper spectra content with Fc around 2k. This is a far cry from the Fletcher-Munson contours, but it makes a somewhat useful sanity check for tonal balance. With a given arrangement I have some idea of the loudness potential and what the perceptual level SHOULD be at a given LUFS value, what I look for when I monitor LUFS is a disconnect between that expectation and the result. This will sometimes point me in the direction of re-evaluating the tonal balance I’ve created for the master, or simply be indicative of an arrangement that does not have loudness potential. The one thing I don’t use it for is evaluating loudness, that’s what the speakers are for.

Which aspect of mastering do you consider your signature sound?

Hopefully an appropriate tonal balance, an involving soundstage, and a treatment of dynamics that is objective and respectful of the program material. If there’s one thing you don’t want as a mastering engineer, it’s having a recognizable sound. If we do our job right it was like we were never there at all from the end listener’s perspective.

Is there a specific mastering project you are most proud of?

My work for Machine Girl over the years has been some of my favorite music I’ve mastered. I am actually working on something for them right now, but it’s kind of top secret. I also adore Terron Darby’s label Dance Artifakts, whose entire catalog I have mastered. Also, there are a few bass producers who have really impressed me over the years with beautiful sound design and soundstaging, Murkury, Pathwey, and Akriza, among others.

What is the best advice you have for producers as it relates to getting the best possible mastering result?

If you want a loud master you need to deliver a mix with loudness potential. I don’t really ask about loudness goals during new client intake, their mixes tell me everything I need to know about where their song can go. If your mix tells a different story than your expectation for the mix you’re in trouble. Loud masters only come from loud mixes, don’t deliver a mix with no microdynamic control and be surprised when you don’t get something back with 10dB less dynamic range. Limiters and clippers are getting more transparent over time, but there is always a breaking point and in my opinion there isn’t much point going past that point, it’s a net negative result that will sound awful in the club and quiet on streaming platforms post-loudness normalization.

Producers should start the process of program loudness on the channel and subgroup level. Putting a limiter on your master channel doesn’t buy you anything that mastering won’t, and odds are we can find a better return on investment for 2-bus processing with our dynamic processing choices. Get the mix sounding big and odds are you’ll get a master back that sounds big too. The outcome is the sum of all the parts, and our ability to undo mistakes made in arranging and mixing is limited, even in stem mastering. Arrangement choices are especially crucial to loudness goals. Mitigating spectral masking through smart arrangement decisions is the number one best way to get a slamming loud master that doesn’t sound awful.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Call your distributor today and ask if they both accept AND pass 24 bit masters on to streaming platforms. If they say no, you should heckle them mercilessly and threaten to switch to a distributor living in the 21st century. 24 bit masters encode to lossy formats more transparently than 16 bit and the mastering community has been communicating that message to distributors for years, being largely ignored. They will listen to their clients though, if enough of them complain.

Where can people find you online?

The usual suspects so far as social media goes, my handle is mattdavis808 on all platforms. I’m on discord more than anywhere these days though, here’s an invite link to the Hacienda server: https://discord.gg/uTUX5mfGkD

[This site is an affiliate of Plugin Boutique and we earn a commission from sales.]